by John Glore

|

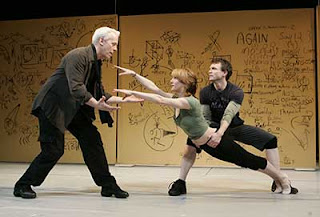

| Paul David Story and Mark Harelik in Red. |

Writing About Rothko

Sometimes, blessedly, something comes fully formed. I walked into the Tate Modern and had no idea I was going to walk out writing a play. I walked into a room with the Seagram Murals for the first time. It was in a larger room, very dark, and there were 12 of them, all the way around. They stopped me cold. It was at a point in my life when I needed something to stop me—really, to stop my life. And they did. I was struck by them, and I gave them time to work on me. I went over and I read the little description on the gallery wall which talks about: “Mark Rothko painted these for the Seagram Building. He decided to keep the paintings, gave the money back, and committed suicide ten years later.” And I instantly thought this was a two-hander play, because, you know, color-field paintings are binary by nature … And so I walked out saying: I think I need to write a play about this.

* * *

I did a year of research before I wrote a word. I read the complexity, the sort of rabbinical, scholarly nature of his diatribes on art, and I thought: that’s what this person needs to sound like. … With Rothko, I knew what I wanted to write about. I knew why I was writing it, which had to do with my relationship with my father. The fact that the characters happened to be painters was secondary to me. And I knew that Rothko was going to have to have a huge speech about people not appreciating his work, people not taking him seriously enough. There’s a long speech in the play … and it ends with “I’m here to make you think, I’m here to stop your heart.” That’s the first thing I wrote, because I knew he was going to have a speech like that. Then I thought: If I could get past that, I could write the rest. So I wrote the hardest part first.

–from an interview with playwright John Logan in the theatre magazine,

Chance

|

| Playwright John Logan |

The main activities in John Logan’s

Red are: talking about painting; preparing to paint; and then beginning to paint. While this might not seem the stuff of urgent drama, the underlying action of the play is indeed urgent, stemming from a profound struggle going on in the heart and mind of painter Mark Rothko. That struggle is made manifest in his volatile interactions with the young man who has come to serve as his assistant, and in Rothko’s relationship to the world outside his studio.

Still,

Red is not a portrait of a tormented artist disintegrating under the corrosive force of his own misunderstood genius (think, the Hollywood version of the Van Gogh story). It’s true, Rothko has his demons, and he will eventually take his own life, but that won’t happen until ten years after the end of

Red. The two-year period in which Logan’s play takes place, 1958-59, is actually the time when Rothko experienced his ascendancy as one of the leading artists of the 20th century.

As the play begins, he has been given a commission—a sizable one —to paint a series of murals that will hang in the newly erected Seagram Building, itself a masterpiece of mid-century American architecture. Rothko should need no further proof that, after 30 years of professional striving and frustration, he has finally arrived. The commission might have gone to any of a number of other, arguably more prominent abstract expressionist artists. But the renowned architect Philip Johnson has come to him, and the honor means as much if not more to Rothko than the money.

“Rothko’s love of the theater informed his works throughout his life; he painted theatrical scenes, admired many playwrights, and referred to his paintings as ‘drama,’ and his forms as ‘performers.’ His experience painting stage sets in Portland may well have influenced the murals he designed years later for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in 1958 and for Harvard University in 1961, and those commissioned by Dominique and John de Menil for a chapel in Houston in 1964.”

-- Diane Waldman, Mark Rothko in New York

And yet … (There must be an “and yet,” or there would be no drama.)

And yet, his success feels terribly fragile. He remains convinced that people don’t understand his work, even if they’re willing to pay top dollar for it. He distrusts the very idea of the artist as celebrity, of art as commodity—but he can’t help feeling perturbed that other artists are more famous, that their work hangs in the best galleries and museums while his does not, that a has-been like Picasso can make a fortune selling misshapen pots and doodles on napkins, while at the same time a new generation of artists breathes down Rothko’s neck, rejecting the tenets of abstract expressionism and looking to replace it with a kind of self-aware, ironic “pop art” that Rothko finds altogether execrable. And the work of those unworthy upstarts—Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, et al.—is hanging in the same galleries that previously exhibited Rothko’s paintings.

So yes, this lucrative commission offers a kind of validation and vindication.

And yet … how can he take the money without feeling that he has sold out to the very anti-artistic forces that he has long vilified? Part of the problem is that the murals are destined to hang not in some grand foyer or dedicated gallery space, but on the walls of the Seagram’s Four Seasons restaurant, a “Temple of Consumption” in the words of Rothko’s assistant, Ken. Rothko has decided that this improbable setting will provide him with an opportunity to confront and provoke the richest, most powerful members of society with his work. A leftist since becoming politicized during the Depression, Rothko enthusiastically embraces the subversive possibilities of this commission.

And yet … “Selling a picture is like sending a blind child into a room full of razor blades,” he tells Ken. And he means it. Although Rothko has a flesh-and-blood daughter (and will soon have a son), he thinks of his paintings as his progeny, to be protected at all costs from unfriendly eyes, uncomprehending hearts and the maws of unscrupulous predators. So how can he consider letting them hang amidst the ravening and maneuvering and dinner-table palavering of New York’s power elite?

That’s what so perplexes and frustrates the young assistant, Ken. An aspiring artist himself, he signed on for this job because of a true admiration for Rothko and his work. Ken has lived his own story of pain and hardship at an early age, which makes it possible for him to understand in a deep way Rothko’s insistence that art must spring from a tragic impulse, that there must be “tragedy in every brushstroke.” Although Rothko insisted when hiring Ken that he had no intention of serving as his mentor, his rabbi, his father-figure or his therapist, he eventually becomes all of those to some degree. The more time Ken spends in the studio, listening to Rothko, working with Rothko, communing with Rothko, the more Ken’s admiration deepens.

And yet …

Although

Red uses art—and the psyche of the artist—as its specific dramatic material, its human concerns are more universal than that. The goings-on in Rothko’s studio, the day-to-day business of a working artist, are fascinating (and in one instance, even thrilling), but they are only the surface layer of Logan’s story of two men grappling with the conundrum of life from two very different perspectives. Ken is just starting out as an artist and a man; Rothko is very near the pinnacle of achievement, a vantage-point from which one inevitably begins to consider the possibility of decline and loss. Ken needs to understand; Rothko needs to be understood. Ken still sees life as a process of addition; Rothko understands that it is inescapably a process of gradual subtraction and simplification (a process that has also informed the development of his art). Ken is young and hungry; Rothko is getting old … but he’s still hungry. Red is about the synergy that arises between them as they pursue a common goal and discover their connection.

|

| Paul David Story and Mark Harelik in Red. |

Red Dream Team

SCR’s production of

Red is staged by founding artistic director David

Emmes. While casting is always a vital aspect of directing, it becomes

especially crucial when a play includes only two characters, one of whom

is a titan of 20th century American art with a larger-than-life

personality and a propensity to be loquacious. Emmes didn’t commit to

taking on

Red until he had found, in Mark Harelik, an actor who could do

justice to the role of Mark Rothko.

Harelik’s

illustrious association with SCR spans 25 years and six previous

productions (along with a great many workshops and readings). He played

leading roles in

Search and Destroy (1990),

Tartuffe (1999),

The Hollow

Lands (2000),

The Beard of Avon (2001),

Cyrano de Bergerac (2004) and

In

a Garden (2010). He has also appeared in New York (where his credits

include the original Broadway production of

The Light in the Piazza), in

regional theatres nationwide, and in numerous films and television

shows. SCR has long considered him to be one of the leading theatre

actors of his generation, and we welcome his return in

Red.

In

some ways, the greater casting challenge came in finding a young actor

who could hold his own onstage with Harelik. Paul David Story makes his

SCR debut (apart from appearing in the NewSCRipts reading of

Death of

the Author) in the role of Rothko’s assistant, Ken. Story has appeared

on and off-Broadway, at such leading regional theatres as Baltimore’s

CenterStage and the Dallas Theatre Center, and on film and television.

A

play about art demands a scenic design of consummate artistry: One of

the finest set designers in the American theatre, Ralph Funicello,

returns to SCR for his 29th season, after having contributed designs for

such disparate productions as

Zealot, Hamlet, Misalliance (twice) and

Brooklyn Boy, among many others. The design team is rounded out by

costume designer Fred Kinney (whose SCR set and/or costume assignments

have included

Sight Unseen, Sunlight, A Wrinkle in Time and

Ordinary

Days) and Cricket Myers (

Mr. Wolf, Zealot, Trudy and Max in Love and

many others) for sound design; but no one thus far mentioned outdoes

lighting designer Tom Ruzika for SCR longevity, as this marks his 40th

year of contributing lighting designs to SCR productions (including all

36 years of

A Christmas Carol).

Learn more and buy tickets